Dear Harvard Law School Class of 2019,

Welcome! I want to take my inches here to write to you a bit about Time.

Time is frightening, because we do not have a lot of it. I probably have even less than you, because I drink too much Diet Coke, which I am told is melting my bones. None of us — even those who can live without the delicious taste of a freshly popped can of calorie-free Coca-Cola — has all the time in the world. Our lives therefore are dramatic and exciting. We get to experience the invigorating suspense of making hard choices about what we want to labor for during our brief and precious time here on this Earth.

When we stop and think about Time, we are reminded that we have to, at some point, not keep our options open. We are reminded that we have to, at some point, not prepare for the next thing. Time invites us to join the counterculture of commitment: to abdicate our throne of open options to instead work day in and day out at some project, be it a cause or a creation, a child or a community, for a sustained period of Time.

This invitation is worth considering because if we do not commit to something, if we do not find our vocation, if we do not listen for our calling, if do not choose a task to work at with our heads and hearts and hands during our time here, then we risk dying in the hallway of open doors, having never walked through one because we feared committing to something imperfect for us.

But nothing worth committing to is perfect for us. And if we wait for something perfect, we will fail to meet the many imperfect, inconvenient, unpleasant — and yet still crucial — challenges calling out to our generation. One in four of our American children grow up in poverty. Our nation’s Congress — the house of the People — has been corrupted by money. A warming globe threatens humanity’s most vulnerable. Folks in neighborhoods across this country are suffering from loneliness. And our legal system is drastically skewed to serve a powerful few at the expense of an exposed many. These challenges need all hands on deck. We need people — we need lawyers — who are going to devote their time to tackling them.

Unfortunately, for every 2014 Harvard Law graduate who pursued work in organizations designed to, as our mission statement impels, “contribute to the advancement of justice and well-being of society,” four graduates joined organizations designed to advance the interests of the wealthiest and most powerful individuals and corporations. Even more unfortunately, only a small portion of folks who choose to work for corporate interest organizations immediately after graduation will ultimately transition to organizations designed to advance the interests of the underdogs.

Each individual’s choice of how they spend their time is their own to make. Each individual’s choice is complicated. I do not dare tell any individual what to do with their time here. But this institutional imbalance between the scope of these great challenges, and the minuscule number of Harvard lawyers who choose to use their education to tackle them, is shameful.

How did it come to this? We at Harvard Law School forgot about Time. We teach the law like it exists outside of Time. We do not discuss the history of how the law got made, the future of how the law could be different, or the present of how the law works in the real world today. In the coming years, Class of 2019, we need your help in again steeping this school in Time.

If we can do better at teaching the history of the law, we can cut the present order down to size, showing how it came to be and how that process was often less reasonable than one would expect. If we stop asking “Why do you think this law is set up this way?” and instead ask “How do you think this law wound up this way?”, we can better remember that the folks who made the present order were no better than we are.

If we can do better at teaching the future of the law, if we can discuss not just how to navigate the legal order, but also how to change it, then we will better prepare ourselves to join our ancestors in co-creating our social order. If we start remembering how much can happen in a generation’s lifetime — how many Constitutional amendments or political watersheds can come to pass in just a couple of decades — we will start valuing not just legal analysis, but also legal imagination.

And finally, if we can do better at teaching the present of the law, if we expanded our curriculum beyond case studies to include direct experience with the realities of the justice system, then we would learn not just how to think like attorneys — advocates for specific clients — but also how to think like lawyers — members and caretakers of the legal profession, tasked with serving the justice system and advancing its public interest mission. (Our only required field trip in my 1L year was to a corporate interest law firm. If you, as a class, can advocate to have yours be to a border detention center or a union hall or a prison, your class will be better equipped to, as we are instructed by Canon 8 of the American Bar Association’s Model Code of Professional Responsibility, “participate in proposing and supporting legislation and programs to improve the [legal] system.”)

We are too often led to believe that some looming threat, be it an invading horde or an insurgent demagogue, is what’s going to be our nation’s downfall. But if our country comes to an end, it will most likely come from something much less dramatic: our failure to sustain the necessary work.

If we can acknowledge Time again, if we can see ourselves as inhabiting a brief and special scene of a great tapestry, then we will be better able to make the commitments necessary to sustain the work with which we have been tasked right from the very beginning of this country: the day-in-day-out, year-in-year-out, generation-in-generation-out civic work of forming a more perfect union.

Our time may be finite, but our challenges are too. And to our immense benefit, our grace is not. And when those three meet, it is a beauty and a joy.

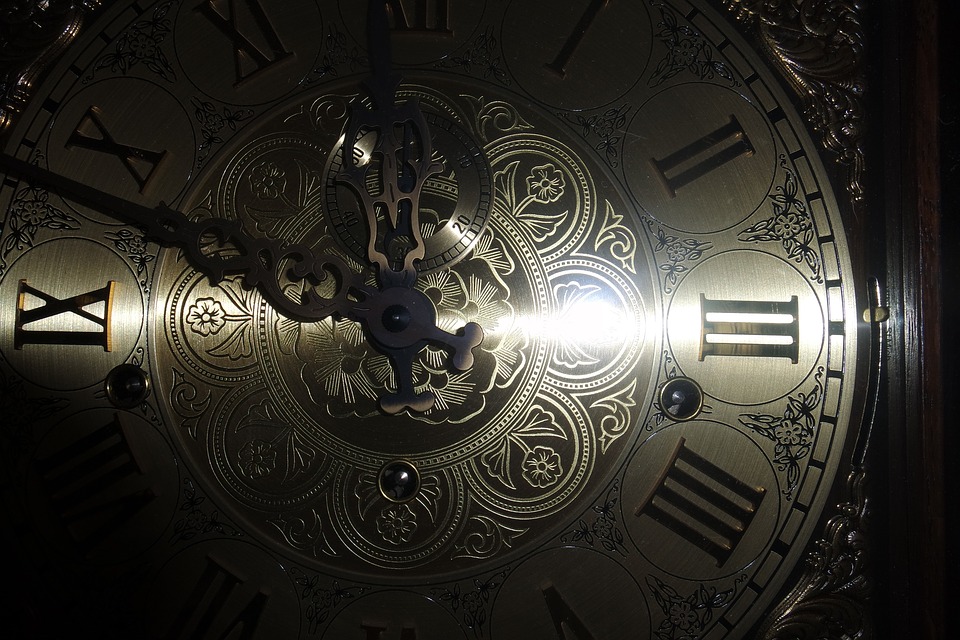

So do not be afraid to take a moment to consider the clock. In fact, your law school years might be the best time to ask yourself, as the poet Mary Oliver once asked, “What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” If you feel too timeless here and forget to answer the question, there are forces that will answer for you. Don’t let them. You have much better ideas than they do about how you should spend your time, both here at law school and in your life after.

Sincerely,

Pete Davis

This piece was a part of the 2016 orientation issue. To read more, click here.